Before Daesh came to the area, we hid the smaller items from the site storage in our house. But then they found out, surrounded the house, and broke in. They held me at gunpoint and threatened to kill my children unless I showed them where the items were.

Conflict antiquities traded in Europe and the US are fueling international crimes in the Middle East and North Africa . State and non-state armed groups in Syria, Iraq, Libya, and Yemen have institutionalized the looting of antiquities as a weapon of war and a major source of financing. Looting fuels ongoing conflicts and enables the commission of grave human rights violations and international crimes.

These crimes will continue unabated & remain profitable so long as there is largely unregulated market for illicit antiquities where the dealers, brokers, & intermediaries operate.

The global traffic in looted cultural objects is at times dismissed as a victimless crime since its harmful aspects are not as apparent as those of trafficking in arms, drugs, or persons. Despite the seemingly benign nature of antiquities, the illicit trafficking of looted antiquities is physically, socially, and culturally destructive. Artifacts are pieces that are often, not only invaluable forms of cultural heritage but also non-renewable resources that can generate income for those who loot and traffic these items for generations.

While looting of antiquities is an ancient phenomenon, over the last decade it has reached a scale not seen since World War II. This escalation is largely due to the ongoing conflicts in the MENA region.

Estimates as to the amount of income that it generates for armed groups vary, but most researchers agree that looted antiquities have become a multi-million dollar source of financing for state and non-state actors alike. This funding enables them to continue to commit atrocities, by allowing them to purchase weapons, recruit and compensate new members, and otherwise support their operations in conflict areas and commission of terrorist attacks elsewhere.

State & non-state armed groups in Syria, Iraq, Libya, & Yemen have institutionalized looting of antiquities as a weapon of war and a major source of financing, which fuels ongoing conflicts & enables the commission of grave human rights violations & international crimes.

So far, policy and regulatory measures, as well as legal proceedings focused on customs violations, tax evasion, or property crimes, have not deterred the illicit trade in looted antiquities.

There is a growing consensus that only criminal prosecutions of the market-end dealers—which would expose their connection to and role in perpetuating war crimes, crimes against humanity, and financing of terrorism—will ultimately put an end to the illegal business, prevent further looting and destruction of cultural heritage, and bring much-needed redress to the affected communities.

In Syria, Iraq, Libya, and Yemen, the pillage of cultural artifacts is part of a larger pattern of conflict-related violations amounting to war crimes and crimes against humanity, including unlawful killings, enforced disappearances, torture, sexual violence, and the destruction of property.

The scale of pillage in these conflicts is overwhelming, making it impossible to document every individual incident.

However, The Docket has gathered detailed information on more than 300 incidents of pillage in Syria, Iraq, Libya, and Yemen within the last decade. Almost two thirds of these incidents involve the pillage of cultural property. The primary actors who conduct or facilitate pillage are either insurgent groups (including designated terrorist organizations) or government armed forces or affiliated groups (such as militias). Groups include, among others, ISIL, Jabhat al-Nusra/Hayat Tahrir al Sham, al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, and Ansar al Sharia.

In Syria

Tens of thousands of items have been pillaged from archaeological sites and at least 40,635 items have been looted from museums. These items include mosaics, relief sculptures, ceramic, stone, and alabaster sculptures, ceramic and bronze tablets, steles, jewelry, and coins.

In Iraq

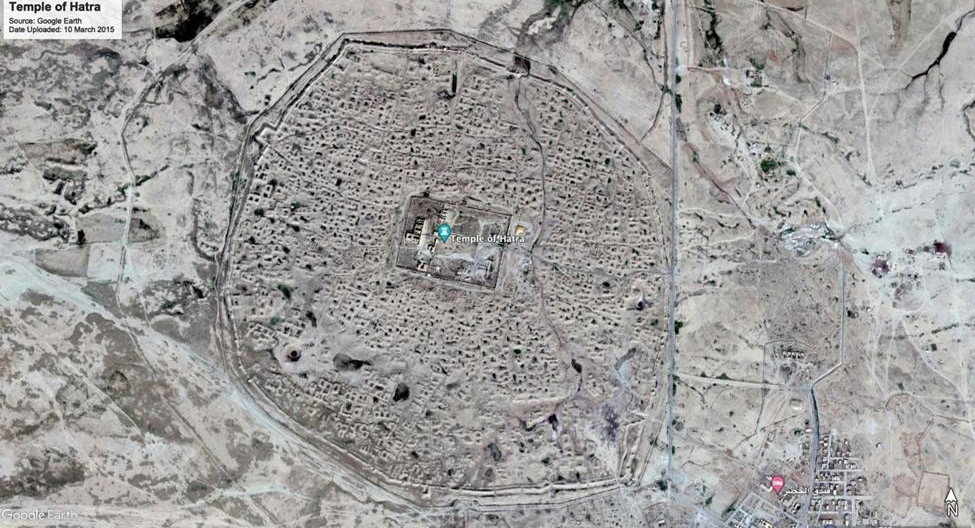

ISIL extensively pillaged the city of Mosul in northern Iraq, including its universities, libraries, and museums; the archeological sites of Nineveh and Nimrud; and religious sites associated with Yazidi, Christian, and Muslim communities.

In Libya

The pillage of cultural property occurred predominantly in the eastern and northern regions, including the UNESCO sites of Cyrene and religious sites associated with Sufi communities in Tripoli.

In Yemen

Ongoing pillage has targeted major museums and archeological sites, including an estimated 12,000 items looted from the Dhamar Museum, 16,000 items from the Military Museum in Sana’a, and 120,000 items from the national museum in Sana’a.

Pillage and destruction of cultural property constitute war crimes under international law and the domestic laws of European States.

In addition to being a crime on its own, pillage is often part of a wider pattern of criminality and a source of income that has enabled ISIL and other armed groups to commit war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity. These crimes have been widely documented and are currently subject to prosecution in a number of domestic jurisdictions.

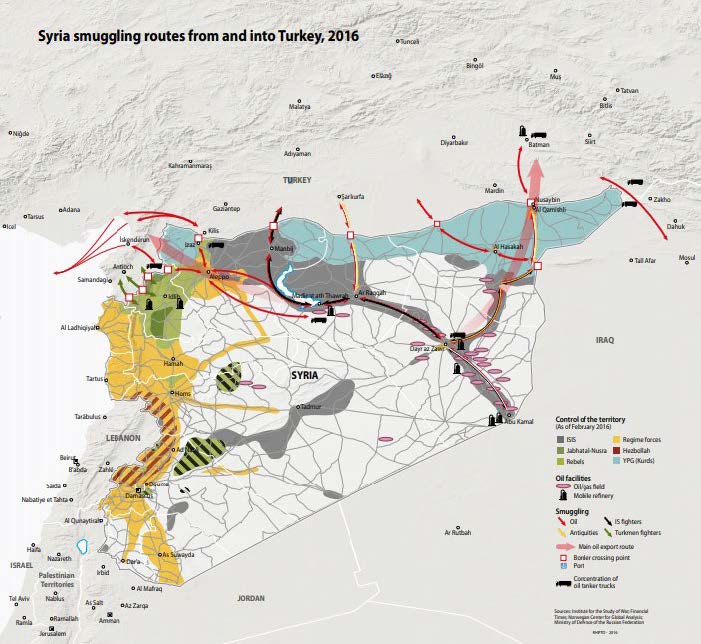

Looted antiquities from Syria, Iraq, Libya, and Yemen arrive in European and U.S. markets via complex international networks that include smugglers, dealers, intermediaries, and brokers across the North Africa, the Middle East, Gulf countries, Asia, and Eastern Europe.

Understanding these routes, as well as those through which armed groups access the resulting funds, is critically important for establishing the complicity of market-end art dealers in crimes committed by state and non-state armed groups on the ground in the source countries. Specific routes vary depending on the country of origin of the looted antiquities. In some cases, they have also changed over time because countries change their laws or enforcement policies to make certain routes harder, thus forcing the networks to look for alternatives.

The two main routes for antiquities originating in Iraq and Syria are Turkey and Lebanon. The Docket’s research has shown that both remain active to date. From Libya, looted antiquities are mainly smuggled through Egypt and Tunisia. From Yemen, the items are mainly smuggled through the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, and Qatar. Other transit portals are East European countries, such as Bulgaria and Romania, as well as Thailand, Jordan, Kuwait, Israel, and Singapore.

Transit countries are essential for the process of “laundering” the antiquities (i.e., providing customs or export documentation to legitimize their subsequent sale).

The UAE, and particularly Dubai, appear to be an important transit point through which items originating in the Middle East and North Africa arrive to Europe and where laundering occurs. Freeports—essentially, tax-free warehouses created to temporarily retain manufactured goods—play an important role in the international trafficking of looted antiquities. In freeports, antiquities originating from any country can be held for an unlimited period of time and at minimal expense until they are released to the market. Freeports, including ones located in Europe and particularly in Switzerland, have been repeatedly implicated in storing looted antiquities.

Finally, over the last decade, the trade in illegal antiquities has also become prominent online, particularly through online auctions and e-commerce websites, as well as through social media platforms. Facebook contains dozens of groups where the trade in questionable antiquities seemingly occurs, & some of the administrators are individuals affiliated with designated terrorist groups. Other social platforms allegedly used to trade in illicit antiquities include Instagram, Skype, & WhatsApp. Hundreds of items are also being sold at online auctions such as Ebay, Vcoins, Trocadero, & others, where annual sales of antiquities far exceed those of offline auction houses.

A number of methods are being used to avoid customs inspections and conceal the illicit nature of the artifacts:

- false declaration of the value of a shipment (lower than market value);

- false declaration of the country of origin of a shipment (a transit rather than source country);

- vague and misleading descriptions of a shipment’s contents;

- splitting a single large object into several smaller pieces for separate deliveries, allowing informal entry and reassembly later after receipt;

- addressing a shipment to a third party, falsely stated to be the addressee or purchaser, for subsequent transfer to the actual purchaser;

- failure to complete appropriate customs paperwork;

- concealing antiquities in shipments of similar, legitimate commercial goods;

- and addressing shipments to several different addresses for receipt by a single purchaser.

For items appraised more than 100,000 dollars, a Turkish dealer would cross into Syria to check the item. Third party would be holding the case, so that the payment can be released once the parties agreed. Sometimes we were contacted by Europeans directly—through an app which allows you to have a foreign phone number. Europeans have their preferences – mainly looking for items from early Christianity, but other items, as long as their authenticity can be verified, are in demand.

The Docket’s research has established that the archeological artifacts pillaged in Syria, Iraq, Libya, and Yemen are trafficked to Europe and the United States via international networks that have been on the radar of law enforcement agencies for decades. Yet these dealers have managed to avoid any significant consequences for their criminal activity so far.

The initial evidence packages have been shared with prosecutors in several European countries and with U.S. law enforcement agencies – specifically, in jurisdictions to which these individuals are connected through their nationality, residency, or business transactions. Where possible, The Docket continues to gather relevant evidence to enable the prosecution of antiquities dealers for complicity in war crimes, financing terrorism, and related charges. The Docket’s work has focused on collecting information that links prominent dealers operating in European and U.S. markets to antiquities pillaged in conflict areas in the MENA region by designated terrorist and other armed groups. Much of this information cannot be shared publicly at present for legal reasons, but this report contains an overview of the available evidence, which points to the need and viability of prosecutions. While this report refers to a few illustrative cases, in which specific individuals are named, it is limited to only the cases that have been publicly reported on—in the media or official statements from law enforcement agencies.

While the legal frameworks differ from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, the criminal codes of most European countries as well as the criminal statutes of the United States contain provisions that allow authorities to prosecute the dealers as either accomplices to war crimes and other international crimes or as financers of terrorist activity. In general, to establish criminal liability in such cases, it must be established that the antiquities were looted by a group involved in criminal behavior and that the dealers knowingly traded in such items, thus providing the funds that allowed the armed groups to commit atrocities.

The problem of looting and illegal trade in antiquities from MENA and other conflict regions has been extensively discussed at international, European, and national level for years.

Multiple policy and regulatory initiatives have been implemented, yet they have had little success in curbing either looting and destruction of archeological sites or the international trade in conflict antiquities. This is largely due to insufficient regulatory focus on the source countries as well as a lack of standardization of measures across transit and market countries, which continue to be easily exploited by antiquities trafficking networks. While market demand drives and enables the entire trafficking chain, the market remains the least regulated part of that chain.

Attempts to regulate it are often undermined by the strength of lobbying groups, and an imbalance of power between market-end dealers and ultimate receivers of the looted antiquities and the communities from which they have been looted. International enforcement efforts have focused almost exclusively, with a few notable exceptions, on the recovery and return of stolen objects to the country of origin.

Seizures and civil forfeitures, however, appear to have no deterrent effect on the dealers. Such penalties are largely perceived as the cost of doing business and, at times, even boost the dealers’ business, since restitutions are seen by the market as proof that the dealer trades in authentic (rather than fake) antiquities. While policy measures, regulation, and restitution are important, only criminal prosecution—particularly prosecutions that result in significant financial losses and custodial sentences—is likely to have the necessary deterrent effect to disrupt the illegal trade of antiquities, prevent further looting, and stem the flow of funds into the hands of terrorist and other armed groups.